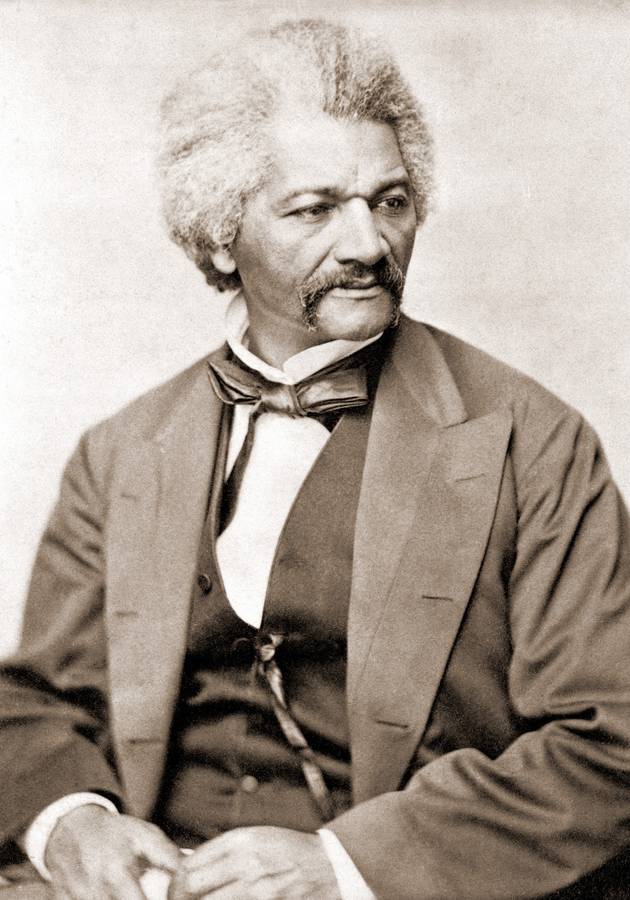

Frederick Douglass lived 20 years as a slave, nine years as a fugitive slave subject to recapture, and almost five decades as “an orator of unparalleled stature,” publisher and editor of an anti-slavery newspaper, leader of the abolitionist movement, acclaimed author of three autobiographies, and a statesman. He lived long enough “to see and interpret black emancipation, to work actively for women’s rights long before they were achieved, to realize the civil rights triumphs and tragedies of Reconstruction, and to witness and contribute to America’s economic and international expansion in the Gilded Age.”

In his 1,000-page Pulitzer Prize-winning magnum opus, “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom,” historian David W. Blight paints a vivid and in-depth portrait of this exceptional and complex man, a national figure in Ireland, Scotland, and Britain – and one of the most important Americans of the 19th century. So, get ready to be reminded of his accomplishments – as we all should, from time to time – and perhaps even learn some less known facts about his life.

Narrative of the early life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave

The extraordinary man now remembered as Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, a slave, in Talbot County, Maryland, in February 1818. He was the son of Harriet Bailey – one of five daughters of Betsy Bailey – and, “with some likelihood,” his mother’s white owner, Aaron Anthony. By slavery’s evil logic, he was separated from his family at the age of 6 when he was transferred to the large Wye Plantation, about 12 miles away from his birthplace. His mother, constantly hired out to other farms, died the following year, probably away from all of her seven children. “My poor mother,” Douglass would write in 1855, “like many other slave women, she had many children, but no family!”

Frederick was a precocious but introverted and solitary child. As a result, he made no close friends among the younger slaves at Wye. However, Daniel Lloyd – the 12-year-old son of the patriarch of the plantation – took a liking in young Frederick’s intelligence and treated him as “both servant and playmate.” Later in life, this experience would drive Douglass to remark that “the equality of nature is strongly asserted in childhood,” noting that Daniel “could not give his black playmates his company, without giving them his intelligence, as well.” Moreover, Frederick was allowed to sit outside the room where Daniel and his siblings learned from their tutor. Inadvertently, he learned as well.

Even more importantly, young Frederick earned another friend at the Wye Plantation: Anthony’s daughter, Lucretia Auld. He describes her as the first white woman who ever bestowed “the slightest word or look of kindness” upon him. Indeed, it was thanks to her pity and persistence that, at the age of 8, Frederick was transferred yet again – this time to Baltimore. He reached the city’s port – aboard the sloop Sally Lloyd – just as the spring of 1826 was about to begin. Little could Douglass know that another spring was about to begin – in his soul and heart.

The unlikely apprenticeship of Frederick Douglass

In retrospect, the move to Baltimore would prove an extremely fortunate move for Frederick – for several reasons. First of all, Baltimore was an urban environment. Secondly, it was not really a “slave city.” At the time Frederick arrived, Baltimore was in the middle of an economic boom, and – as more workers were needed – more immigrants arrived, and fewer people remained in slavery. As the free black community grew in numbers (from 10,000 in 1820 to 18,000 in 1840), the slave population was dwindling (from about 4,500 in 1820 to 3,000 in 1840). Last but not least, Frederick was supposed to live in Baltimore with the family of Hugh Auld – Lucretia’s brother-in-law – and be the boyhood companion of his son, Tommy Auld. Indeed, he was treated as such by Tommy’s mother, Sophia.

Sophia Auld hadn’t owned slaves before Frederick. So, for a time, she treated him “more akin to a mother than a slaveholding mistress” and allowed him to feel like a “half-brother” to Tommy. She fed and clothed him properly and even started teaching him the alphabet and reading to him from the Bible. But then, her husband Hugh found out about these lessons and severely reprimanded his wife in front of Frederick. He told her that literacy was “unlawful” in Maryland for slaves, and that “learning would spoil the best nigg*r in the world.” If Douglass learned to read, Hugh reportedly said, “there will be no keeping him,” as education would “forever unfit him for the duties of a slave.”

Sophia “felt the force” of Hugh’s remarks and, “like an obedient wife, began to shape her course in the direction indicated by her husband.” Unexpectedly, Frederick did the same as well. Hugh’s chastisement of his wife may have changed his immediate fortune for the worse but changed his worldview for the better. As Douglass would later write in “My Bondage and My Freedom,” Hugh’s burst was “the first decidedly antislavery lecture” he had the opportunity to hear in his life.

The episode made him realize the power of education and inspired him to purchase a secondhand copy of “The Columbian Orator” – a book he would later call his “rich treasure” and “noble acquisition.” A collection of political essays, poems, and dialogues, “The Columbian Orator” was widely used as a textbook in American schoolrooms at the time. Douglass made it his own: it became his constant companion and his most prized worldly possession.

Frederick Douglass’ journeyman years or, the renunciant

Between the ages of 12 and 20, the Aulds hired out Frederick twice – first to farmer William Freeland and then to Edward Covey. On Freeland’s farm, he started educating other slaves to read the New Testament at a weekly Sunday school; the congregation was dispersed permanently after other plantation and slave owners found out about their slaves being educated. On Covey’s plantation, Frederick spent perhaps the worst years of his life. The new master – “a noted slave-breaker” – whipped him so regularly that his wounds rarely had enough time to heal. “I was broken in body, soul, and spirit,” Douglass wrote in “My Bondage and My Freedom.” “My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed; the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; behold a man transformed into a brute.”

At the age of 20, Frederick decided that he had enough of it. With the assistance of a free black woman named Anna Murray – with whom Douglass had fallen in love a year before – and a couple of friends from Baltimore, he fled the city – and slavery – in September 1838, after disguising himself as a sailor and boarding three different trains and three different boats to New Bedford, Massachusetts. During this daring escape, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey decided to drop his two middle names and change his surname to Johnson. Just a few days later, partly to evade slave hunters, he made another alteration and became Frederick Douglass, both a fugitive and a free man.

As Frederick Douglass, this former slave would become the most photographed and – along with Mark Twain – the most widely traveled American public figure of the 19th century. He would grow to be a powerful orator, the national leader of the abolitionist movement, and the author of three widely admired autobiographies, all classics in the genre. A firm believer in the equality of all people – regardless of color, race, or sex – Douglass would also turn into one of the earliest supporters of women’s suffrage. Even so, his relationship with both women and suffragettes was a bit more complicated.

Wives, lovers, and ménages à trois

On September 15, 1838, Frederick Douglass married Anna Murray. The two would remain married for the following 44 years, until her death from a stroke in 1882. In the first ten years of the marriage, Anna would give birth to five children: Rosetta, Lewis, Frederick Jr., Charles, and Anna (who would die at the tender age of 10). Afterward, however, she would have to fight with two rivals for her husband’s attention, both of them white European women: British abolitionist Julia Griffiths and German feminist and freethinker Ottilie Assing. Both of them were extremely important friends and co-workers in Douglass’ life. Assing was probably even more: a lover.

Recently immigrated from Germany, she first visited Frederick Douglass in 1856, a year after he published his second biography, “My Bondage and My Freedom.” She was initially interested in the German translation rights for the book, but as time passed, she grew more interested in Douglass’ intelligence and body. “For many summers between the late 1850s and 1872, Ottilie Assing came to Rochester and stayed in the house as Frederick’s intellectual and emotional companion,” informs us Blight. “How this ménage à trois functioned for so long still remains, in part, a mystery.”

What isn’t mysterious at all is Assing’s opinion of Anna, whom she held “in utter contempt, disrespecting her lack of education, and even at times privately denigrating her role as homemaker.” She had secretly hoped to force Douglass to divorce Anna and marry her instead, firmly believing she was a better match for him. This never happened: shortly after Douglass became a widower, he eloped with yet a third white woman named Helen Pitts, the copyist in his office.

Just a few months later, Assing committed suicide, swallowing cyanide in a public park in Paris. Despite drawing a lot of criticism from both the public and within his family, Frederick’s interracial marriage with Helen would prove to be a happy one – the two would remain married (and childless) until Douglass’ sudden death from a heart attack in 1895.

The turbulent path to emancipation

Douglass’ marriage to Pitts scandalized America in the dying decades of the nineteenth century – but not nearly as much as it would have just several decades ago. Unquestionably, this was, in large part, thanks to Douglass himself, his actions and pursuits, his advocacy for freedom, his talents as an orator, and his never-ending struggle for justice and equal rights.

He first made a mark at a Nantucket antislavery convention, on August 12, 1841. No record exists of what he actually said that morning, but based on numerous testimonies, his speech was so poignant and heartbreaking that it immediately catapulted him into renown. American reformer Samuel Joseph May remarked that, on the occasion, Douglass “gave evidence of such intellectual power – wisdom as well as wit – that all present were astonished.” “I shall never forget his first speech at the convention,” prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison would write four years later. “I think I never hated slavery so intensely as at that moment.”

Tall, handsome, sonorous, and knowledgeable, “Douglass took the abolitionists’ traveling circuit by storm in the early 1840s.” At the insistence of Garrison – a towering influence upon the mind and opinions of the young Douglass – he published his first autobiography in 1845. It was a risky move, since he revealed in it both the name and the location of his former owner – who still had the right to reclaim possession.

To avoid recapture, Douglass left on a two-year speaking tour of Great Britain and Ireland. In the meantime, his friends raised 150 pounds – or, precisely, $711.66 – to purchase his freedom. The money was sent to Hugh Auld, who sent back a document announcing the manumission of “his slave Frederick Bailey, alias Douglass.” The document ended with the following sentence: “in other words, these papers will render him entirely and legally free.”

Lastly a free person, Douglass returned to the United States with fewer cares, more courage, and enough money to start his own antislavery newspaper. He named it “The North Star,” and published it under the ultraprogressive slogan: “Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and all we are Brethren.” The newspaper earned him many new admirers but resulted in the severing of ties with Garrison, who disagreed with the need for a separate black-oriented press. But Garrison’s time was passed – it was now Frederick Douglass’ turn to rouse the crowds.

Abolition war, abolition peace

In 1852, Douglas gave his famous Fourth of July speech before a racially mixed audience of approximately 600 people in Rochester, New York. In it, he described the United States constitution as “a glorious liberty document,” full of “principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery,” passionately accusing his contemporaries of betraying the ideals and values of the Founding Fathers – and, thus, of betraying their own country as well.

Douglass’ “antislavery interpretation of the constitution” was the basis of his initial disagreement with President Abraham Lincoln, who – for a time – didn’t regard “biracial democracy” as possible in the United States; Lincoln was more supportive of the idea that, once freed, black Americans should voluntarily move to a foreign country, preferably a newly created one in Africa or the Caribbean.

However, in time, the President changed his opinion, and Douglass became his consultant during the Civil War. He advocated for the war to be framed as a direct confrontation against slavery and saw most of his efforts crowned on the first day of 1863, when Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation declared, “all persons held as slaves [within the rebellious states] are, and henceforward shall be free.”

Unfortunately, Douglass’s plans for the creation of a second American republic came under threat after the assassination of Lincoln. His successor, Andrew Johnson, was “a staunch white supremacist who accepted the end of slavery but could not abide the idea of black civil and political rights.” As a result, Douglass campaigned for the election of Ulysses S. Grant as president in 1868; with Douglass’ help, Grant managed to further the cause for equality and protect the newfound rights of the black population in the South.

An alternative nation

Throughout the Reconstruction, Douglass also vigorously supported the women’s rights movement. In 1848, he was one of the few men – and the only black person – to attend the Seneca Falls convention, the first women’s rights convention in the United States. This remained a matter of lifetime pride for him, as did the fact that he was among the 32 men and 68 women who signed the “Declaration of Sentiments” – in the words of historian Judith Wellman, “the single most important factor in spreading news of the women’s rights movement around the country in 1848 and into the future.”

However, Douglass did let some the suffragettes down two decades later, when he was working with other Republicans to pass the Fifteenth Constitutional Amendment, which gave black men – but not women – the right to vote. As a result, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony publicly broke ties with Douglass; he never truly reconciled with the latter.

After the Reconstruction, Douglass became first a marshal and then recorder of deeds of the District of Columbia. In 1889, he was appointed U.S. minister and consul general to Haiti, a position he would hold for the following two years, before resigning in July 1891. Two years later – and just as many before his death – Haiti made Douglass a co-commissioner of its pavilion at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was a woeful and even absurd sight, regretfully comments Blight.

“On a cold night in Chicago,” he writes, “the most famous black American warmly embraced the bloodiest nation-building story in the history of the Americas. In a United States where lynchings were now constantly in the news and Jim Crow laws emerged from Southern legislatures, Douglass stood as the spokesman of the once dreaded legacy of the Haitian Revolution. At Chicago in 1893, this American patriot, sickened once again at the power of white supremacy, needed an alternative nation to celebrate.”

Final Notes

Only remarkable biographies can do justice to remarkable men. Blight’s account of Frederick Douglass’ life is, undoubtedly, a biography that deserves such a description. We cannot recommend it enough.

12min Tip

George Santayana once said that those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it. And history is often but the biography of great men – such as Frederick Douglass.